Oh hi there!

I hope your week is off to a great start. If it isn’t, I’ve got some great kid table vibes for you. If it is, I’ve STILL got some great kid table vibes for you. This week, I’m seeing:

Excitement about the little things

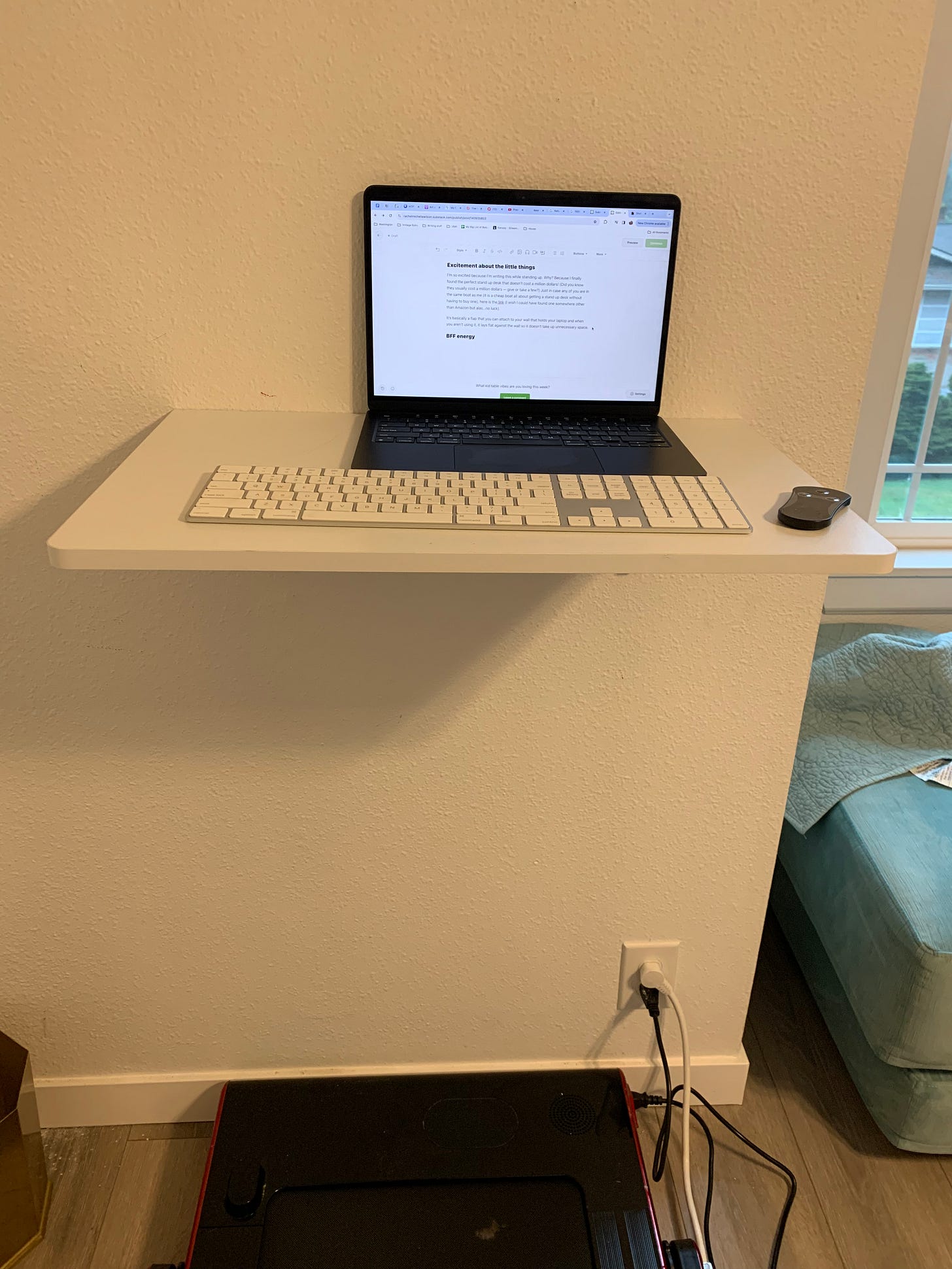

I’m so excited because I’m writing this while standing up. Why? Because I finally found the perfect stand up desk that doesn’t cost a million dollars! (Did you know they usually cost a million dollars — give or take a few?) Just in case any of you are in the same boat as me (it is a cheap boat all about getting a stand up desk without having to buy one), here is the link (I wish I could have found one somewhere other than Amazon but alas…no luck).

It’s basically a flap that you can attach to your wall that holds your laptop and when you aren’t using it, it lays flat against the wall so it doesn’t take up unnecessary space. I put a treadmill under mine. The space is still in progress but this is a huge step!

BFF energy

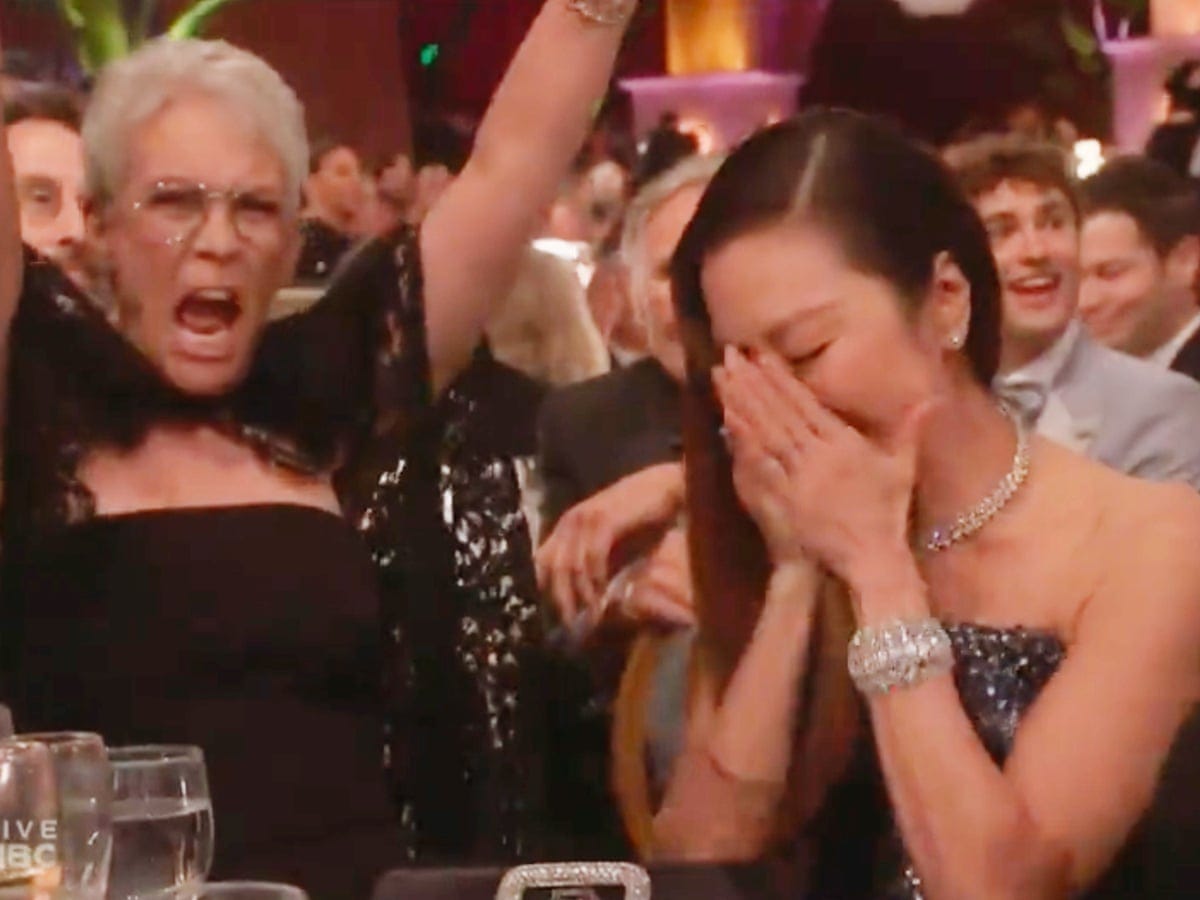

I love this Oscar moment between Jamie Lee Curtis and Michelle Yeoh. Which person do you think won the award?

Michelle Yeoh! BFF kid table vibes look like JLC.

This week I feel honored because I get to be a JLC for a friend whose been a JLC for me in countless ways. CONGRATULATIONS TO ANGELA PHAM KRANS for winning the prestigious Asian/Pacific American Picture Book Honor Award! If you haven’t read Finding Papa, I highly recommend it. (Thi Bui’s illustrations will knock your socks off.)

Honoring the funny

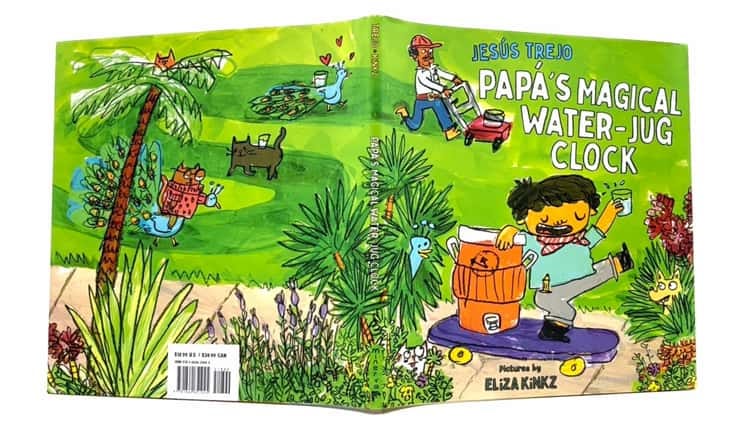

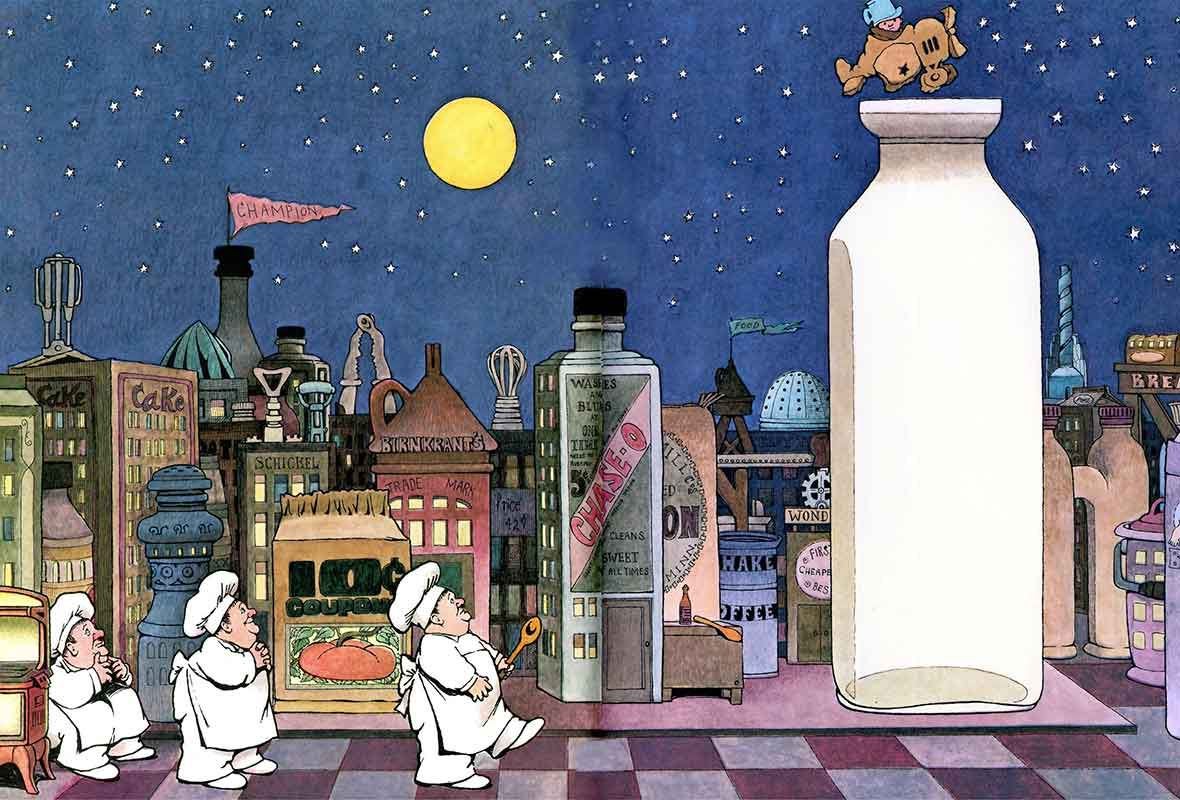

Earlier this week, I was chatting on Substack Notes with the talented illustrator

about how it would be so cool to have a comedy award in children’s books…and THEN the very next day her AMAZING illustrations from Papá's Magical Water-Jug Clock by Jesús Trejo won the Pura Belpré Youth Illustration Honor. Sending some JLC vibes to Eliza as well! I love it when comedy genius is honored!Honest feelings

Award seasons can come with a lot of feelings — excitement, jealousy, hope, fear, anxiety, perfectionism, happy tears, discouragement, etc. I’m guessing because I don’t have any books out yet (not until October 15! Woot woot!), I haven’t experienced some of the challenging emotions associated with the awards (yet…dun dun dun). BUT those feelings are human and I’ve experienced them in other ways. If you are feeling any of those things (related to an award or not), I highly recommend reading this post by

about great ways to handle it (definitely subscribe to his newsletter full of gold).What kid table vibes are you loving lately?

This week, I’m sitting at the kid table with…

…children’s book author-illustrator Maurice Sendak! Again!

Thank you so much for all the love you gave part one. It makes me happy that I get to geek out about the stuff I love with you. Somehow in the first week, we’ve already hit 200 podcast downloads. I had no idea what that meant, so I looked it up and supposedly that means we’re in the top 25% of podcasts! Wow! Whether that is actually true or not, thanks for listening :)

Alright, shall we dive in to part two? (I can’t hear you, so I’m going to assume you said yes.)

Note: You can listen to this as a podcast episode or read it below.

Learning from the great Maurice Sendak: Part Two

Welcome to part two of our Maurice Sendak study. Part one was all about his life, influences, and work. (You can check out part one here.) For part two, we’re exploring eight things I learned from his creative process and philosophy. Whether you are a reader, a book maker, or a cool cat looking for inspiration, I crafted this episode to have something jazzy just for you.

8 THINGS I LEARNED FROM MAURICE SENDAK

1: Telling the truth is a risk worth taking.

Sendak’s storytelling is best summed up in his words: “I think what I’ve offered was different but not because I drew better than anybody or wrote better than anybody but because I was more honest than anybody. And in the discussion of children and the lives of children and the fantasies of children and the language of children, I said anything I wanted to…I don’t believe in this demarkation like ‘you mustn’t tell them that’…If it’s true, you tell them.”

Well, he definitely told the truth about anger and the difficulty of parent-child relationships in Where the Wild Things Are, and…it received pretty bad reviews at first. Sendak responded to the backlash in his Caldecott Medal acceptance speech (yes, most people came around eventually) by sharing his dislike of “half-true” children’s books that offer “a gilded world unshadowed by the least suggestion of conflict or pain, a world manufactured by those who cannot—or don’t care to—remember the truth of their own childhood.” He argued that these books were more concerned with not frightening adults and had “no relation to the way real children live.”

Using Where The Wild Things Are as an example, he concluded: “The common wish to protect children from their everyday fears and anxieties [is] a hopeless wish that denies the child’s endless battle with disturbing emotions…The book doesn’t say that life is constant anxiety. It simply says that life has anxiety in it.”

I love his speech so much because I think we are often afraid that telling the truth means hopelessness. But for Sendak, telling the truth meant acknowledging that darkness and light exist together and that true hope comes from representing both on the page.

After reading Wild Things, the great writer and mythology genius Joseph Campbell said he loved it because, “It is only when a man tames his own demons that he becomes the king of himself, not the world.” Sendak consistently took risks by facing his demons and sharing the truth about his experiences. To this day, his stories allow kids a safe space to do the same.

2: Always remember you don’t know anything.

When interviewers asked him questions like, “What makes a good children’s book?” he always answered the same way. “Well how would I know?”

It seems to me like this allowed him to maintain a learner mindset throughout his life.

Which actually leads me to the next one…

3: You are never too old to learn.

“It’s a constant fountain, a source of refreshment, to go to the masters. They have done so much that we can learn from.”

Throughout his life, Sendak loved learning from others. Even in the last few years of his life, he was talking with interviewers about what he was reading or listening to and describing the stories he wanted to tell. He took inspiration from books, comics, plays, music, and family and his studio was full of objects “to keep in the mood of whatever” he was working on. (Like a fragile brontosaurus his nephew built for him.)

Sendak was an atheist but he considered some of his inspirations as “wonderful gods who have gotten me through the narrow straits of life.”

He especially loved William Blake, partly because he couldn’t fully understand him. “I guess it’s the way his profound belief in something sounds kind of idiotic but I believe him. I believe in his passion.”

He delighted in Mozart: “ I am in conjunction with something I can't explain…I don't need to. I know that if there's a purpose for life, it was for me to hear Mozart.”

He carried a pocket book of Emily Dickinson everywhere he went. “She is so brave. She is so strong. She is such a passionate little woman. [After reading three poems], I feel better,” he said.

He loved Alice in Wonderland so much that he stole a copy from his cousin. “It’s a terrifying book; it’s a nightmare. That to me comes as close to the world of childhood as great books do. Carroll was allowing for nightmare, murderous impulses. I don’t know why he got away from it. He told the truth about childhood, about how unsafe it was.”

Interestingly, he disliked Peter Pan because of “the sentimental idea that anybody would want to remain a boy…this was a conceit that could only occur in the mind of a very sentimental writer that any child would want to remain in childhood. It’s not possible. The wish is to get out.”

But every creator he admired had the same quality: what he called “authentic liveliness.”

(For those interested, some other inspirations included Schubert, Hugo Wolfe, Palmer, Proust, Eliot, Middlemarch, Randolph Caldecott, George Cruikshank, Ludwig Richter, Wilhelm Busch, A. B. Frost, Edward Windsor Kemble, Ernst Kreidolf, Hans Fischer, André François, Watteau, Goya, Winslow Homer, Mahler, Beethoven, Wolf, Wagner, Verdi, Walt Disney, James, Stendhal, D. H. Lawrence, and Melville.)

4: Let your other obsessions inform your work.

Animation was a big inspiration for his work. He loved making his illustrations dance off the page like a flip book.

Music was also a major part of his process; Sendak couldn’t live without a record player, and the music he listened to informed his work. He said, “Depending on what I’m doing at the moment, there is always a specific kind of music I want to listen to. All composers have different colors as all artists do. And I kind of pick up the right color from either Haydn or Mozart or Wagner while I’m working. And very often I will switch recordings endlessly until I get the right color and the right note and the right sound and then settle down happily into whatever I’m doing.”

He often drew parallels between art forms. Like one night he was listening to Wagner’s “Die Meistersinger” and though he knew it by heart, this time he heard something fresh. He explained that Wagner “in some mysterious way, had made the atmosphere—the very night air—of Nuremberg into music. I could see the city and smell it. And that’s the kind of thing I want to convey in my illustrations. The pictures should be so organically akin to the text, so reflective of its atmosphere, that they look as if they could have been done in no other way. They should help create the special world of the story. When this kind of drawing works, I feel like a magician, because I’m creating the air for a writer.”

Isn’t the idea of creating the air so beautiful?

5: Understand your why.

Sendak didn’t like the term “children’s books” and preferred “books that children like.” He said, “I don’t write for children. I don’t write for adults. I just write.” He often said things like he didn’t believe in childhood at all. There are many interpretations of his philosophy, but when taken together, I think he meant he believes in children as whole people with complicated interior lives, capable of feeling all the big feelings an adult experiences. He didn’t like it how they were dismissed as “children.” Basically he wanted them to get more credit.

Here are a few quotes to back that up:

“There is something about this country that is so opposed to understanding the complexity of children. It’s quite amazing.”

“I’ve always had a deep respect for children and how they solve complex problems by themselves. [And how do they?] Through shrewdness, fantasy, and just plain strength. They want to survive. They want to survive.”

“Grown-ups desperately need to feel safe, and then they project onto the kids. But what none of us seem to realize is how smart kids are. They don’t like what we write for them, what we dish up for them, because it’s vapid, so they’ll go for the hard words, they’ll go for the hard concepts, they’ll go for the stuff where they can learn something, not didactic things, but passionate things.”

But here is also a quote that makes it all quite confusing:

“I don’t write for children. I write. And somebody says, that’s for children. I didn’t set out to make children happy or make life better for them or easier for them. [Do you like them?] I like them as few and far between as I do adults. Maybe a bit more because I really don’t like adults.”

But then here’s another quote that clears it up:

“You cannot write for children. They’re much too complicated. You can only write books that are of interest to them.”

What a rollercoaster! I think he’s saying that he doesn’t feel like his books are meant to provide answers or teach kids. He’s just trying to write an interesting book that’s truthful. Because that’s great literature and that’s what they deserve.

6: Respect your audience, especially your inner child.

Sendak didn’t idealize childhood at all. He said, “Too many parents and too many writers of children’s books don’t respect the fact that kids know a great deal and suffer a great deal.” And he believed, “the magic of childhood is the strangeness of childhood.”

He remembered being “a creature without power, without pocket money, without escape routes of any kind [who] didn’t want to be a child.” Because of this, he always tried to “draw the way children feel” instead of focusing on what he called “the naturalistic beauty of a child.”

When talking about the process of trying to honor the child, he said (long quote but worth it): “All I have to go on is what I know—not only about my childhood then but about the child I was as he exists now. You see, I don’t believe, in a way, that the kid I was grew up into me. He still exists somewhere, in the most graphic, plastic, physical way…One of my worst fears is losing contact with him. I don’t want this to sound coy or schizophrenic, but at least once a day I feel I have to make contact.”

He continued, “The pleasures I get as an adult are heightened by the fact that I experience them as a child at the same time. Like, when autumn comes, as an adult I welcome the departure of the heat, and simultaneously, as a child would, I start anticipating the snow and the first day it will be possible to use a sled.”

He explained that it wasn’t always easy to connect with his inner child. When his creative process wasn’t going well, he said: “I get a sour feeling about books in general and my own in particular. The next stage is annoyance at my dependence on this dual apperception, and I reject it. Then I become depressed. When excitement about what I’m working on returns, so does the child. We’re on happy terms again. Being in that kind of contact with my childhood is vital to me, but it doesn’t make me perfectly certain I know what I’m doing in my work.”

Even after winning the Caldecott, Sendak didn’t let an award affect his deep respect of children. He said, “Why would any book be good for all children? I mean no grown up book is good for all people so we mustn’t assume that a book that won a Caldecott is appropriate for every child reading it.”

But he did love it whenever a child would react positively to his work. He said when creating books his first priority was to always “reach and keep hold of the child in me” and second to reach his audience.

7: Respect the object.

To facilitate the best reading experience, Sendak believed books needed to be designed and treated like a beautiful objects. He said, “Reading is a physical act….Every book that is manufactured should have textures and qualities and smells as though it were a toy. As though it were something precious. And then when you’re read to by a parent…you have the whole thing….parent, child, and book fusion. That’s something television or any other form cannot give a human being.”

His deep respect for the object included bookmaking. He said, “If one picks up a book and is dazzled by the beauty of the book and nothing else, one has failed….It should harmonize so that you cannot separate the book from the binding, the endpapers, the title page, the typeface on the title pace, the frontispiece. It should all become so blended, so uniform that the feeling is that there is positively no other way this possible could have been done.”

Doesn’t that inspire you to learn more about book-making? I’ll never look at a book the same way again.

8: Respect the craft.

Because of his respect for his audience and the form, Sendak took his craft very seriously. He asked himself, “Why would a child turn the page? A child isn’t polite. I mean adults will conscientiously read a book they don’t like because they feel they should. Children don’t feel any such compulsion. If they hate the first two pages, its ‘whamo’ against the wall. They don’t care if its won 18 Caldecott awards…so you’ve got to catch them. You’ve got to catch them in a rhythmic pattern, a syncopation that makes them turn that page.”

Continuing with the music metaphor, he said, “You got to catch them with your metronome right from the start so they syncopate with the book…Children hum and move when they’re reading a book and they’re turning pages and looking for pictures. The timing has to be intuitive to an incredible degree.”

This is why he called writing “tremendously difficult” and spoke of the incredible patience making books required as sometimes it took him 5-10 years to complete a book. What kept him going? His “permanent dissatisfaction,” the need in him “to achieve something of incredible height for [his] sake,” and the fact it made him happy. He said, “[Making books] is the only true happiness I’ve ever ever ever endured in my life. It’s sublime. Its just going into another room and making pictures. It’s magic time. Where all your weaknesses of character and blemishes of personality and whatever else torments you fades away.”

Perhaps my favorite quote from him on craft is this: “The art of illustrating is like any other art, the art of growing up into oneself.”

I hope you enjoyed our study of Maurice Sendak. I learned so much and felt so inspired; I hope you did too.

If you want more Sendak, I received a bunch of additional resources from wonderful commenters and compiled them here on my blog (you’ll see a section at the bottom called “Additional resources recommended to me by cool people).

Thanks to Whiskey Geraldine for our podcast music as well as Joanna Rowland, Marietta Apollonio, and Angela Pham Krans for sponsoring this episode. To become a podcast sponsor, you can upgrade to a paid newsletter subscription.

Thanks for sitting with me at the kid table. Until next time!

As always, I’ll save you a seat right next to me.

Your exploring-ways-she-can-connect-with-her-inner-child friend,

Rachel

Share this post